Claire is a member of Plan C London.

I don’t know about you, but my social media feed is exploding with accounts of sexism and violence right now. It has been quite a month for us Feminists On The Internet, that is for sure.

First, there was the incredible, largely anti-trans, response to proposed changes to the Gender Recognition Act. A response that gave renewed buoyancy to previously dead-in-the-water kinds of thinking about the right for trans people to exist at all. Then, the #metoo hashtag brought forth a wave of seemingly endless stories about gendered assault and violence experienced especially (but importantly not exclusively) by women.

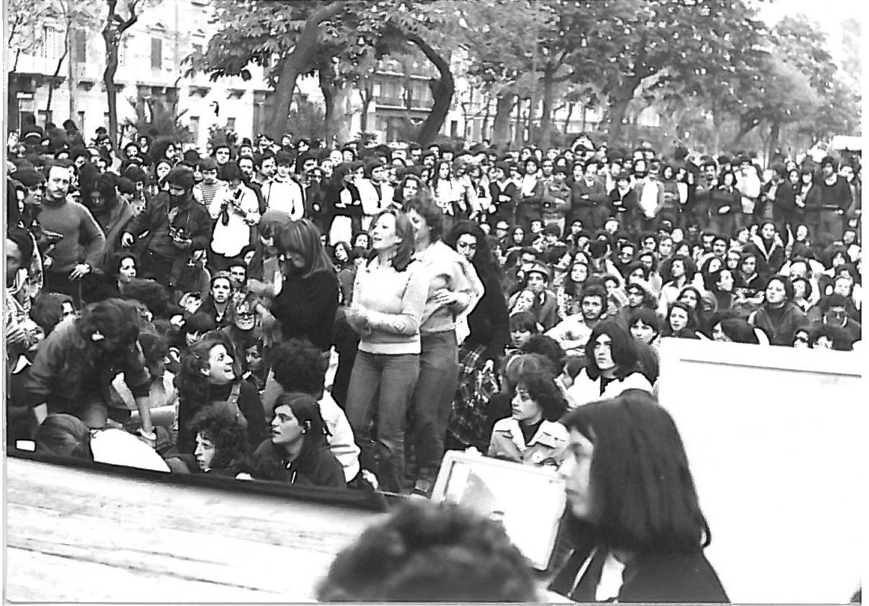

I’m going to try to relate these issues to each other, through my experience as a queer activist, and as someone intimately acquainted with the issues raised by #metoo. I want to talk about what we on the radical left might do with all these bad feelings. I also want to make it clear that we need to take these individual experiences of pain and vulnerability and use our righteous rage to form a collective vision of the future we deserve. One experiment I’m involved in which faces this head-on is the emotionally intense but also inspiring organising meetings of the (trans and non-binary inclusive) Women’s Strike set to take place on March 8, 2018. Collective organising meetings like this are prefigurative, have the hallmarks of the consciousness raising groups of the 1970s, and crucially make political space for us to reconfigure ‘womanhood’, and perhaps also ‘personhood’ in ways that we all desperately need.

For the last few weeks there has been an ugly and heated debate around the UK’s Gender Recognition Act, 2004 (GRA) and current proposals to change the Act. Changes that would make it easier for trans people to have their gender recognised by law, through self-declaration, which basically mean without the need for a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria. In 2016, the parliamentary committee report on the issue suggested ‘Britain has a long way to go to ensure equality for transgender people in the NHS and other institutions’. As a result, there were calls to review the Gender Recognition Act[1] to ensure the process became less medicalised and moved away from framing gender recoginition as an illness. Politicians from across the political spectrum now support these changes, even Teresa May[2].

Jeremy Corbyn is correct in his assessment that the current act is an “intrusive” process, which requires a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, the passing of an interview panel, and to have been socially transitioned for a period of two years[3]. More than 30 recommendations were listed in the parliamentary report, many of which criticise the way transgender people are treated by authorities and the NHS. Pointing to institutional failures to provide equal access to health services. The report found that trans people experience high levels of daily abuse and this undermines their careers, living standards and health.

So it hardly seems controversial then that we might want to improve these systematically transphobic institutions? It turns out to be surprisingly controversial. Add into the mix, all the emotive, sexualised and/or gendered news stories, (take for example the debate around same-sex marriage happening in Australia at present), suddenly everyone wants to talk about children. Please! Won’t somebody think of the children? Well, indeed we might. Given that, from what I can tell, there are no proposed changes to the GRA that relate to anyone under the age of 16, there is little reason to hype up the experience of trans children at all in the debate about GRA. However, MPs do support reducing the age limit for official recognition of a new gender without parental consent from 18 to 16. So, we can only assume, for now, that these are the young people (16 and 17 years) those opposed to changing the GRA are referring to.

This hardly seems worth making a fuss about. However, there have been lies and disingenuous ‘facts’ circulating in radical feminist circles, to such an extent that people who are new to the issue and only just trying to understand what is at stake in this debate are being totally misdirected[4]. One example I encountered of this was equating the prescription of hormone-blockers to teenagers as ‘sterilising children’. In actuality, it’s true that to produce the necessary biological material that you might later require to gestate or produce blood-related children at some point you need to go through puberty, but this is not the same as sterilisation. A teenager postponing puberty so they feel comfortable in their own body is not a young person being sterilised. Let’s not forget the actual history of sterilisation. In that there is an incredible erasure occurring in radical feminist claims of this kind – of the way that women of colour and women with disabilities have actually faced and continue to face forced sterilisation up until today. Equating young people’s desires to postpone puberty with sterilisation is not only unwise and an example of bad science, but it’s outright offensive.

Many of the criticisms made by the parliamentary report of the GRA were made of the NHS. Many women from both sides of this debate work in the NHS. Health care workers are reproductive workers and disproportionately the work of care and health falls to women. At this moment, when the NHS is being privatised and shrunk, when the caring element of the NHS is being quantified and monetised, we cannot fall into the trap of fighting over the ruins of the welfare state. We don’t lose a damn thing by demanding more. We must fight for what we need. It is beyond obvious that at this moment, at the moment of crisis, we need our trans comrades if we are ever to save the NHS. Feminists working in the NHS must embrace trans liberation as part of our work to save the NHS. Acting together is our only hope. It is through struggle that we will forge the necessary connections and bonds of solidarity, not through essentialist and reactionary understandings of gender.

In the middle of this confused and misdirected moment, radical feminists organised a meeting at London’s Speakers Corner to try and coordinate their fight against the GRA. The meeting was entitled ‘What is Gender?’. Although there are conflicting reports online, including claims of physical violence, it is important to remember that a woman having her phone shoved away, even if she is older than the person who shoved her, is not entitled to film the faces of trans people. The fear of being ‘outed’ on the internet has specific ramifications for trans people. As Action for Trans Health stated, ‘outing’ individuals of trans experience on the internet puts that person’s safety at risk, potentially their housing, their family relations and their jobs at risk. It is not to be condoned or minimised. In this case, it’s a form of violence against women.

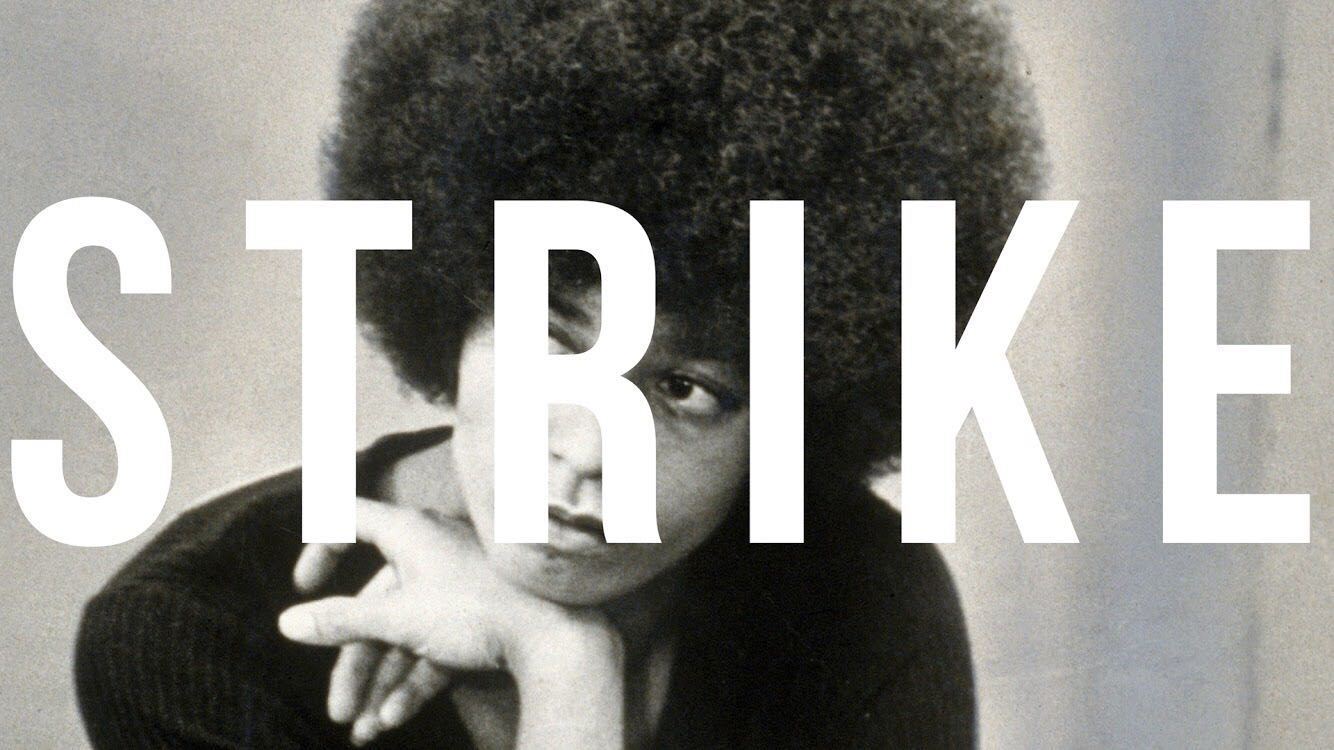

To speak of violence against women, is to also speak of the recent #metoo social media campaign. According to the BBC, the hashtag, #MeToo, has been used more than 200,000 times since Sunday night. Before we rush to politics of the new, it is necessary to note that the hashtag actually began in 2006-07 as a result of the work of black feminist Tarana Burke. She was working with young black and brown girls in the American south and was trying to find resources for them as survivors of sexual violence and ways of sharing their experiences of sexual violence[5]. The term gained momentum recently after actor Alyssa Milano asked victims of sexual assault and harassment to come forward in a show of solidarity following the multiple allegations against Harvey Weinstein[6].

The response was utterly overwhelming. Because it was organised via social media, it was at times difficult to read, both vulnerable and at the same time performative. Problematically constituted as bad things that happen to gendered individuals, albeit on a mass scale, with no push to organise collectively against the systems and structures that create the conditions for violence. It caused many people to have to take time off from social media because it pressed too many buttons in relation to their past. It also gave birth to the hashtag #itwasme where those who have engaged in sexist, violent or aggressive behaviour towards women could put it out in to the world, repentant and apparently committed to change and to behave ‘better’ in the future. Neither survivors nor perpetrators were exclusively one gender. However, as writer Charles Clymer, who has been the victim of rape, wrote, although both genders suffer abuse “there’s a specific misogynistic component to rape culture.”

It is this specific misogynistic component that must be mobilised against, and it must be done so collectively. What this incredible volume of stories tells us is that violence is systemic, and cannot be beaten via individualised accounts online. What we need to do is take this anger, this disappointment, this rage and this sense of earned feminist righteousness to the centre of power. We have to change our society. One way to do this is to build for the International Women’s strike on March 8 2018. I suggest this not just as an organiser and participant, but because the very process, dare I say praxis, of meeting together regularly to discuss the way that our gender shapes our experiences and our lives (and we discuss everything, from the menopause to passport checks in maternity wards to domestic violence to the sexist nature of children’s television) – this a collective process of transformation. For decades, women have met together to discuss the way that sexism impacts upon their lives in ‘consciousness raising groups’ (an example of Plan C engaging with this is here[7]) and found it to be incredibly empowering. It is important to make this assembly as broad as possible in terms of participation.

The fact that in 2017 the, Morning Star[8] saw fit to publish an article entitled ‘The Gender Identity Debate Explored’ is laughable. There is no gender identity ‘debate’, or at least there ought not be. People are the gender they say they are. When people arrive at the Women’s Assembly we don’t ask what you were ‘raised as’ or what junk is in your underpants and then go on to make wild and clumsy extrapolations based on that information. And neither should anyone else. We assume they are there to participate in the Women’s Assembly. Unless they signpost that they are here to do other jobs like childminding or cooking, jobs that are being undertaken by men and some non-binary people as their contribution to the work of the Women’s Assembly.

Presenting as women brings all kinds of additional labour. Everything from the fact that we are expected to be pretty (trans women are often expected to be even prettier!) to the tiresome work of being expected to listen to our bosses patiently about their marital problems and never expect the same in return. Women’s labour is exploited in multiple ways and a women’s strike is about building the counter-power to fight back against the multitude of issues facing women, non-binary and femme people. You can learn more about last year’s strike and the demands here: https://www.womenstrikeus.org .

The Women’s Strike is about more than just the withdrawal of our paid labour or work – it is also about recognising that women take on a disproportionate amount of unpaid work in the form of cooking, cleaning, caring and other tasks that are essential to the day to day functioning of society. We also face a particular kind of violence and oppression that needs to be fought and organised against through an intersectional praxis. If you think everyone, regardless of their gender or identity should be able to walk the streets, day or night, without the fear of violence or assault, join the Women’s assembly next Thursday evening in either Birmingham or London[9] or form one in your own city. We would be more than happy to help you organise because it is the kind of work that will change all of our lives, possibly all of our genders too.

Claire – Plan C London

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jan/14/transgender-people-being-let-down-by-nhs-say-mps

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/oct/18/theresa-may-plans-to-let-people-change-gender-without-medical-checks

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jul/07/2004-gender-recognition-act-nicky-morgan

[4] <iframe src=”https://www.facebook.com/plugins/post.php?href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fjbardrosenberg%2Fposts%2F10102473819582890&width=500″ width=”500″ height=”269″ style=”border:none;overflow:hidden” scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ allowTransparency=”true”></iframe>

[5] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-10-19/me-too-a-beginning-not-an-end-of-fight-against-sexual-abuse/9065814

[6] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-trending-41633857

[7] http://www.weareplanc.org/blog/c-is-for-consciousness-raising/

[8] But actually also in 2016, as part of a trend in their journalistic practice: http://www.morningstaronline.co.uk/a-f7db-Why-I-wont-accept-the-politics-of-gender-identity#.WeiZ0mJSx-U

[9] https://www.facebook.com/events/1858060754506221/?ref=br_rs