Plan C has an ongoing commitment to the Social Strike as a strategic and theoretical orientation. This interview hopes to contribute to that process by focusing on the experiences of struggle and the ideas generated by struggle that the Social Strike is based on.

The interviewer is Callum Cant, Plan C Brighton, and the interviewee is Al Mikey, Plan C London.

Maybe we should start by outlining the lineage and the history of the Social Strike as an idea. In my mind, the first precursors of the Social Strike are probably autoreduction movements in Italy in 1974-75. What kind of history do you see behind the term?

The Social Strike has gone through various terminological changes over the years. Negri talked about the ‘Metropolitan Strike’ in 1995 after observing a three week-long French transport workers strike, during which he noticed how social life adapts to crises. For example, there was the problem of routine. Cities run on trust. We trust that a bus will turn up, that a train will turn up, that we can get to work – and once that kind of level of trust goes people have to find alternative means of organising social life. There was a huge amount of self-organisation going on just in terms of people getting from A to B. So there was a form of cooperation between the workers, who were making the strike by not going to work, and the service users, who were making the strike through self-organisation.

But like you said, there are roots in the Italian struggles of the 1970s. In 1976-77, in Turin, Lotta Continua used the slogan: Take Over the City. They basically recognised that there was a limitation to workers’ struggles, especially when there was co-ordination between landlords and factory owners. At that time, that when workers won higher wages from the bosses it was just basically absorbed in higher rents taken by the landlords. The linking of struggles in the productive and reproductive spheres was an idea that really emerged out of the Autonomia movement in general. And so whilst it might not be explicitly called the social strike, there is quite a long history below the surface.

If this idea has been around for so long, why are people looking to act on it in this form now? What are the conditions that the current wave of social strike thinking and acting is responding to?

I mean I think in the Italian context, the specific terminology of the social strike is quite new – maybe five years old. Parts of the Italian left continue to fetishise struggles over production in a specific locality as the absolutely fundamental part of class struggle, so there has been a general movement to try and open this conception up and bring social movements into connection with workplace struggles. In the last four/five years, a new generation of activists have put great emphasis on this.

I think a lot of the impetus to do so has come through coming up against the limitations of social movement politics, and also the turn towards logistics as a point of disruption in the political imaginary. People have begun to understand how capital circumvents struggles in the process of circulation, in a spatial, global way. Those two experiences, I think, have brought people back to the ideas and praxis around social strike.

It’s interesting that you don’t mention the 2008 crash as a factor – is there a reason why? Because for me I guess, in the UK context it seems to be a definitive moment.

In terms of the 2008 crisis, its important to recognise that in Italy, even though the crisis did have a very material effect on most people, especially young Italians, in terms of movement events the anti-austerity movement didn’t really take off in the same way, as an event, as it did in the UK. Even though people do reference it as the general crisis of capitalism, it’s not necessarily got the same relevance. The social strike could have existed before 2008 and it would still have made sense.

I remember when I was in Italy in 2004, there was a strike of transport workers, and that was politicised and socialised quite massively, especially in Rome. There was a night demonstration which led to the occupation of a large empty factory that was then used as a social centre, and it was called Strike. So these ideas and practices were circulating before the crisis.

In the UK it’s different, because in 2008 we were a left that had been in decomposition for a long time. The biggest far left group – the Socialist Workers Party – was imploding, and that gave space to a lot of new organisations that looked critically at how the left had fared in the crisis, and also looked at the fact that the left itself was in crisis.

When we look back at 2011, when the first co-ordinated post crisis strike action was called by the TUC on pensions in the public sector for June 30th, there was quite a big build up. At that point there had yet to be any really sizeable reaction to the crisis, apart from the student movement. We had a G20 meeting of finance ministers in East London at the Excel centre in 2009, and 10,000 people rioted. But the student movement was the only organic movement that had emerged in response to the crisis. A lot of the discussions around at the time was around waiting for the Trade Union movement to move, for people to go out on strike.

Those experiences in 2011 I think really educated a lot of people. We basically discovered that our capacity to go on strike was minimal, because there was a whole bureaucratic layer that was preventing strike action. But at the same time, a lot of people still saw strikes as the pinnacle of a response.

From 2011 onwards there were obviously anti-austerity demonstrations and fragmented struggles around housing and other crisis-related stuff, especially around migration, perhaps antifascism as well. But there was still this central issue of power and counterpower that wasn’t being addressed. So when we started discussing the social strike in London, it was very much located relative to the fact that we didn’t have power.

Traditionally, power came from mass collective action at the point of production, but we couldn’t replicate that, because we ourselves weren’t involved in it, or if we were, we still struggled to get people out on strike, because it was a process beyond our control. So the social strike was in effect something that emerged out of lack of power, and looked at how potentially we could develop, articulate and exert power.

Talking of lack of power, what kind of formative movement experiments and failures let you to be convinced of the necessity of the Social Strike? Was the failure of the TUC strikes in 2011 as a response to the 2008 crisis the biggest?

Yeah for sure, I think for the left in general it was an important failure because there was a lot of discussions around the left press about a general strike (discussions that went beyond the usual suspects, who call for general strikes every week). Organisations like the Socialist Party and the Socialist Workers Party were lobbying the TUC to call a general strike, and at the time I remember we were thinking: well, a general strike is kind of impossible at the moment. Apart from co-ordinated strike action in the 70s and 80s, the last actual general strike was 1926, and that was a colossal failure for the Trade Union movement.

It was totally sold out by the TUC.

Completely, and after that they lost millions of members, there was a process of regression in class power. So the TUC was never something that could utilised to accelerate the struggle. The best we could hope for was they they could be forced into calling a general strike as a gamble. The TUC is stuck in an obstructive mindset. But at the same time they’ve got a massive membership and potentially a massive capacity of disruption.

So there were two big strikes in 2011. We had June 30th, and November 30th. At the time we were organised through an ad hoc collective, that was formed specifically for those strikes. This collective decided to call a ‘Generalise the Strike’ assembly. We had 150 people attend, a large number of them with links to the Spanish 15M movement who were camped outside the Spanish embassy in solidarity with the movements in Barcelona and Madrid. So from there we tried to start to create a discourse about participation: who is allowed in, who’s allowed to utilise the strike weapon?

Following that we had multiple assemblies leading up to both strike days, and then on the days themselves we organised two blockades, one in north London, one in south London. The idea was that we would basically march from picket to picket. In the end it involved 200-300 people in each blockade, with sound systems and stuff. There was already this idea of opening up strike participation, trying to find our way towards a general strike.

Because of trade union laws, unions could only go on strike on issues that crossed all the unions and all sectors, that why they chose pensions, and in terms of union membership, only people already in unions could go on strike, which reduced the technical capacity for a general strike through existing legal frameworks. That was our critique at the time. The left is calling for a general strike, but it’s technically impossible, therefore we need other means to open up that space and use our disruptive capacity.

We created a logo which was actually adopted by all the major trade unions, which was quite a big win. They used our hashtag, and there were assemblies in ten cities across the country, with about 600 people involved, and also we had this online platform to geomap all the pickets that were happening. The trade unions weren’t even putting that info out publicly, so we had to find the info by crowdsourcing it on social media. We actually got contacted by around 250 shop stewards to share information on their local pickets.

But we didn’t have any kind of permanent group, that was the problem. To get 250 shop stewards contacting you and wanting to be involved is a rare thing, but this was pre-Plan C, so we had no permanent organisation that came out of the experience that could continue the momentum.

So, talking of organisation, who calls a social strike? Is it an ecology, a network, a party, a system of assemblies…?

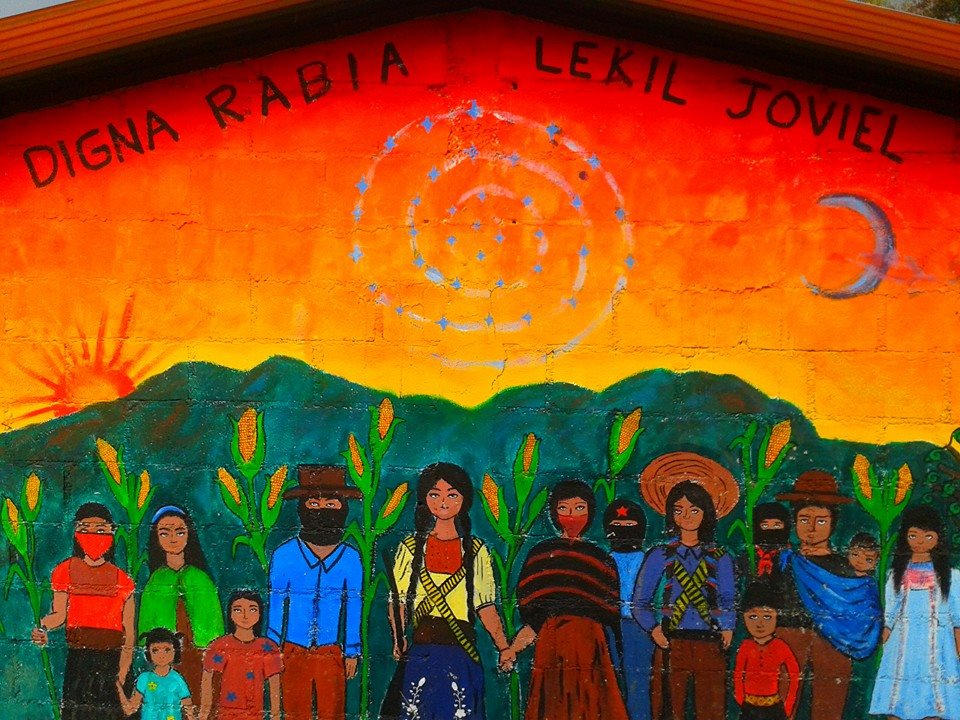

In Italy you’ve still got political unions, unions that came out of the 70s when they split from the main unions, that are meant to operate on a democratic level (although that’s a bit dubious sometimes). Base Unions like Cobas, SiCobas, FIOM, and they all have aspiration to wider popular struggles and wider political struggles against capitalism – really explicitly, against capitalism. FIOM have developed these things called ‘social coalitions’, which basically involve anyone and everyone, from social centres to migrant groups to civil society groups and other trade unions. That perhaps provides a basis.

If you want the Social Strike to involve certain sections of people, they you have to organise them from the beginning. It dictates a level of participation far beyond the traditional strike processes. For me, an ecology of groups is a fundamental basis for the Social Strike.

You talk about who’s getting involved – who is the Social Striker? Socialised worker, multitude, surplus populations, precariat, working class. . . is there even one composite revolutionary subject that you could identify?

EuroMayDay is another precursor of a lot of the contemporary social strike stuff, and one that was quite heavily concerned with questions of subjectivity. So basically when we were having radical May Days in London in 2000/2001 they featured about 10,000 people, and that inspired a lot of similar May Day demonstrations across the world, away from the tradition labour movement organisation. In Italy a group of activists in Milan decided to do a May Day in a shopping centre, and talk about precarity and the changing nature of class composition and so on. And from that developed a set of discussions on a European level on treating May Day as a historical reference point for workers’ struggles, but also trying to understand the necessary departure from that history in the contemporary context. And a lot of discussions of precarity developed from that – the term precariat was actually coined as a joke by activists in Milan, as they were going through this process in 2002/2003. EuroMayDay was the first time that we managed to establish a European network to talk about these issues distinct from major trade unions, and work on questions of inclusivity and the construction of revolutionary subjects.

There was a lot of radical cultural production, looking at personas and who is invisible and marginalised in struggles. A lot of this focused on migrant labour, women, precarious workers, elderly people and the like. These were the subjects, the potentially radical subjects, that were excluded from traditional struggle but still central to capital accumulation. So when we talk about subjectivities, I always think about that really, looking for people who are excluded, without excluding the people who are already included, like organised labour.

So it’s a subjectivity defined by facing outwards rather than turning inwards? Whereas with Operismo’s Operia Massa [Mass Worker] you would internally, positively define that as like a FIAT worker in Turin or something, with this subjectivity you would define it by the negative externality of who is not included elsewhere. Is that fair?

Yeah, there is an obvious kind of tension with that, that has manifested in certain demonstrations in Italy, between the Mass Worker and the young precarious workers. At some points there is a clash of interests. A lot of these younger workers want a lot more, they talk about more stuff, whereas those people in unions with very specific demands don’t want loads of scruffy youth running about talking about communism.

But this idea of being expelled from security is a kind of common motif. It comes from a critique of how unions have turned from a movement of the working class into a bureaucratic business partner of capital, as happened all over the western world in the 80s. They began to exist to provide their members with a decent standard of living and not concern themselves with anything beyond that. There is a certain mistrust which comes with this self-interest of people who are by default included. Materially they have a lot more to gain, especially when there is a growth in the economy, compared to people who are excluded. 2008 kind of put that back to square one, but it still exists in some ways.

So, the big question, how do you define the Social Strike?

I would define a social strike based on, first of all, a realisation of itself as a political project. It’s something that has to be thought about, before it can exist.

I’d also define it in terms of a strike which doesn’t contain itself based on the current configuration of struggle, that looks beyond current constraints, like the historical baggage of workers’ struggles and trade unionism and its incorporation into mechanisms of labour management. Social strike both critiques and transcends that absorption, its completely against the co-management of labour and capital, and so it’s inherently a lot more radical.

In terms of the social aspect of it, its a strike that attempts to articulate the social character of conflict. So referring back to J30 2011, then we had strikes in a period when everyone was talking about anti-systemic politics, but the strike was really only about pensions. The trade unions only opposed the more aggressive elements of capitalism, rather than articulating the social reasons why people go on strike. These demands are constrained within a legalistic framework – they don’t talk about time, quality of work, desire, and doesn’t talk about all the other components of someone’s life, and all the people who are not going on strike.

So for me, social strike is this generalising process of antagonisms that goes beyond the initial conflict between labour and capital in direct production and into society.

It seems to me that the major problem facing us now, in a way, is that there are very few forms of associative forms of life available to us. Neoliberalism tends to have demolished them, and has left us with a poverty of community and association. We need to recompose the communities and subjects that will then exert power by striking. Do you agree with that analysis?

Completely. When some of us in London starting talking about social strike stuff, we looked back at the origins of the strike as a concept and a tactic. We looked all the way back to William Benbow, in the 1830s, and how he envisaged the strike being both the withdrawal of labour, and also a process of composing an alternative system.

The first attempt at a general strike in a UK context was to be called the Grand National Holiday, in August 1840. It never actually materialised, but it imagined instituting a new system through the time recovered from work. I think Social Strike very much draws on that dual character of both withdrawing labour but then also developing autonomous infrastructure that allows you to live differently, even if only temporarily. There is a process of creating an alternative system, and every strike acts as an accelerant for the construction of this alternative. That, for me, is really fundamental.

So Social Strikes could function as accelerants for the construction of those forms of life that we now lack?

For sure, this has been this history of class struggle for the last thirty or forty years. Movements of rupture can open up a hole, and change all of social life. This is what happens when you have struggles that go beyond a narrow focus on pensions or wages. The example I referenced earlier of the transport strike in Italy in 2004 and the occupation of a social centre that came out of a socialised strike shows this dual character really well. Social Strikes are as much about constructing an autonomous social life as they are about withdrawing labour.

Finally, where is the Social Strike project at today?

Currently lots of people involved in the Trasnational Social Strike platform are in Paris, viewing the ongoing struggle there through the lens of the Social Strike. They’ve written some really good articles on the situation there. I think that’s the most exciting node of development at the moment.