A Member of Plan C Brighton reflects on the context and implications of the ban.

The ridiculous and reactionary decision to proscribe Palestine Action should be opposed by all means necessary. In the face of UK military and industrial support for an ongoing genocide, direct action to halt the machinery of war is a valid tactic of protest and resistance. Such, at least, is our starting point.

In response to such tactics, the state could prosecute participants for criminal damage without having to use the Terrorism Act to proscribe whole organisations. The choice to go above and beyond simple criminal damage prosecutions and deploy anti-terror legislation is a political one that has wider implications for the movement and is another symptom of a disturbing trend. The proscription of PA marks another step in a dynamic that has been unfolding for 25 years, and which looks set to intensify.

Bringing ‘the war’ home

In the context of the UK, we can trace a phase change in relation to the way the state legislates and acts against terrorism. This change occurs during the time of Tony Blair and his Labour Government. The then Home Secretary, Jack Straw, introduces the Terrorism Act of 2000 which forms the basis for the current powers of our state. What’s important to note here is that this is before the ‘war on terror’ that begins with 9-11 and the Twin Towers bombings.

Within the context of the UK, the phase change in anti-terror laws arrives as a result of the peace process in Northern Ireland. Prior to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, the main role for anti-terror legislation had been in the context of that war. In 1973 the Prevention of Terrorism Act was introduced and the next year expanded. Prior to this act, the British state had a Prevention of Violence Act in 1939 that was introduced to counter the IRA declaration of war in January of that year, and an active sabotage plan it had initiated. Plainly, for a long time, the Irish resistance was the primary target of British anti-terror legislation. This was the situation prior to 2000.

Then came a transition period. When the Irish liberation struggle was moved away from armed resistance with the Good Friday Agreement, the British state introduced the new Terrorism Act in such a way that you might be forgiven for thinking it was a kind of housekeeping. Just as the 1939 Act had expired and been replaced by the 1973/4 Act, so that was in turn replaced by the 2000 legislation. However, even if we were ludicrously generous in our interpretation of the intentions behind the 2000 act, historical events were about to capture it and make it part of a far wider political dynamic.

After the transition period between 1998 and 2000 the next moment is the arrival of the war on terror. To understand the post-2000 dynamic of anti-terror legislation, it’s crucial to realise that the war on terror was brought home by the UK government. It behaved and spoke about its legislative activity as though it’s response to the war on terror was a natural extension of the 2000 Terrorism Act.

Over the course of the next twenty-five years, the definition of terrorism has become an increasing part of the political toolbox of the ruling class, far beyond anything that existed prior to 2000. We’ve had parliamentary Acts about terrorism in 2001, 2005, 2006, 2015 and 2019. The 2015 act noticeably introduced the so called Prevent measures into public bodies in the form of a duty, and this has spread throughout education and social services.

This ‘duty to prevent’ was politically another key shift, introducing a requirement to snitch on a wide range of public employees. Your teacher, lecturer, social worker, they are all basically legal obliged to snitch on you. The whole frame of ‘Prevent’ training has also introduced a model of mental pathology as the explanation for terrorism – extremism isn’t a political issue now, it’s framed in terms of mental health and ‘care’. The Prevent training targets key behaviours as indicators of potential problems and makes the workers in the public sector who have to fulfil this duty feel as though what they’re doing is part of a broad ‘duty of care’, rather than a duty to snitch.

Mission creep towards authoritarianism

Within this historical context, we can find an increasing reliance on the concept of terror to counteract political resistance, both at home and in anti-colonial struggles. We don’t need to see any huge conspiracy here, what we have is rather something like a politically convenient common sense. This is now widely embedded in the social consciousness.

It’s become politically suicidal for mainstream political voices to try and dissent from the governments’ identification of something as terrorist. Liberal voices therefore find themselves unwilling to counter this slow slide into increasingly vaguely defined anti-terror laws and activities. This leaves the space for an easy win for more authoritarian elements of the ruling class who know that all they have to do is play the terror card, and they can effectively get away with repression.

Politically speaking, it’s a matter of pragmatics – it’s easy and usually effective to play the terror card against resistance. It mobilises a whole range of ‘civil duties’ and easily gets the actual machinery of the state – whether in the hard repressive side or on the soft ‘caring’ side – to fall into line and obey orders, all whilst feeling like they’re doing their civic duty rather than being a little Nazi.

The ease of use of this political tool shouldn’t be overlooked. At one point it was a widespread idea that when a politician got into political trouble then a little war and patriotic fervour was a potential tool to use to survive. Of course, making war meant actually sending soldiers to die, which they would unfortunately do, which then meant that there was a political cost to using this tactic and long term counter-effects from the impact of war veterans on society.

With the war on terror the politicians had a tactic that had fewer costs than an actual war, was almost as easy to use to generate patriotic fervour and bolster political support for the ‘strong leader’ and that was incredibly flexible and adaptable to various different opponents. This adaptation and pragmatic value have led to our politicians increasingly using anti-terror talk in an ever wider range of situations.

The reality of this vile political pragmatism is that a widespread common sense has been generated against a vaguely defined notion of terror. Politicians have created an intellectual and social context in which authoritarianism can easily breed and grow. In effect, something like a mission creep has occurred which is then weaponised by authoritarian politicians because they can present themselves as both mainstream (anti-terror being common sense) and more effective (they’re stronger and more direct and can therefore protect society better).

It’s within this context that a Labour government – once again – has taken a pragmatic act that fully sits within the broad common sense of anti-terrorism, but at the same time extends and shifts the terrain as a result. The proscription of Palestine Action should be seen within this context, as the stupid, pragmatic, and cowardly use of an inappropriate tactic to counter political resistance.

Inversions and counter-tendencies

The state is not an abstract body sitting outside our lives, it’s peopled and populated with our neighbours and friends. The University lecturer who sits chatting about the moral failure of capitalism may well also be fulfilling their Prevent duties, at least to the extent that they don’t lose their jobs. The assumption is often that the liberal University environment is effectively pretending and not really enacting Prevent. Similarly with regard to teachers, social workers and others employed in caring spaces, particularly spaces in which young people are present. The reality is more complicated.

The world is a dirty place and people mostly follow the law, even if their compliance is as minimal as needed to prevent self-harm. Often the issue is ignored, and a kind of conscious forgetting is in place. At other times, the cost of compliance becomes too personally challenging for it to continue. The trouble is that this often results in individualised responses, as people decide that it’s enough and move on, or perhaps flame out in a brief moment of resistance. Collective resistance to authoritarian social policies, however, is more difficult.

At the moment we’re seeing strategically important shifts in the situation, as in the case of resistance to ICE in the US and analogous resistance to deportations in the UK. These are yet to become mass movements, but there is growth in this area of resistance – infrastructures and ideas are being experimented with and assessed, albeit in a disparate and local way. In addition, the return of the very concept of a fascist state, albeit in a new form, has clarified the stakes. It’s plain that authoritarians are no longer bit players in modern political life, rather they have taken on the mantle of rebels and resistance against the very authoritarianism that has allowed them to grow in the first place.

This itself is the result of the production of counter-tendencies. The origins of the authoritarian politics we are surrounded with may well result in large part from the use of the anti-terror tactic by liberal politicians (very broadly understood). The trouble is that the authoritarians can use this common sense set up by the liberals to their advantage. On the one hand they can point to the authoritarian state as the enemy, with claims about the great lockdown, woke ideology, indoctrination and elite over-reach for example. They then use this to connect to an amorphous sense of resistance to the state, whilst on the other hand they can present as being better at using such authoritarianism against the ‘right’ enemy. The ruling class has deep divisions in terms of its political strategy, in large part as a result of opening the door to authoritarianism through the generalised introduction of an anti-terror common sense.

At the same time as there are counter-tendencies generated inside the ruling class, there are also counter-tendencies to the anti-terror common sense developing. When the costs of compliance with vague authoritarianism becomes high enough, more and more individuals are faced with a personal choice as to what they can live with. People are increasingly being forced to choose between compliance and resistance, rather than being allowed to just avoid the issue as part of their self-preservation.

Counter-attack

For those within the anti-capitalist resistance movement, broadly defined, the proscription of Palestine Action presents challenges. In the short term, there will be a need for solidarity work and political support for such activity. It’s important to remember, however, that rotten tactics sometimes produce rotten results for those using them and as authoritarianism has come to the fore, so has its face been increasingly revealed as incompatible with the civic duties it has to call upon in order to achieve compliance.

There is a subtle difference between widespread compliance with measures such as Prevent, which might be justified by self-preservation and claims about minimal harm and ineffectiveness, and the active conscious implementation of a policy that you know results in serious harm. If you know that snitching to the state means that someone will be going to a concentration camp, the choice of compliance is more complex. More resistance occurs, more choices to resist take place, the common sense becomes less common.

It’s this common sense that needs to be the real focus of counter-attack. The reality is that something is very rotten in a supposedly liberal secular state when it is even possible to use anti-terror legislation against long-standing tactics of political resistance. Property damage and sabotage are elements of what’s considered the normal range of political action. The attempt to rule out a specific form of tactic not because it’s criminal and breaks a law but because it is terrorism is a direct attempt to constrict the legitimacy of what counts as acceptable politics.

The use of the anti-terror legislation against Palestine Action is in itself unacceptable, but the more fundamental problem revealed by this measure is the political common sense that has been set up as a condition for such action. Put bluntly, the deeper problem is the very fact that Yvette Cooper knows that her actions can all too easily be presented as normal, rational actions of a liberal politician. It should not be possible for this to be the normal state of things and resistance to the proscription of PA needs to push back against this background common sense framework of so-called anti-terrorism.

The key target of counter attack is therefore the overwhelming common sense that has been generated as a result of the ‘war on terror’.

Tactical considerations

Whilst strategically we may need to undermine and sow divisions within an established common sense, in the immediate the resistance movement also faces tactical considerations with regard to effectiveness and survival. At what point, we need to ask, might a specific tactic be met with the deployment of anti-terror measures? We must ask this in large measure as a question of self-protection. What did PA do, what threshold did they breach in the enemies minds that prompted the turn to this tactic of repression?

Let’s clarify that this is not a matter of blame. It’s not a question of PA somehow going out of their way to trigger anti-terror actions. We’re not victim blaming here, only trying to get a sense of the state of play. To do this it’s worth considering the similarities and differences between this instance of direct action and others, as well as the particular tools the state has deployed.

To begin with the tools the state is using, it’s perhaps useful to consider the definition of terrorism within the proscription legislation. It specifically mentions a very broad category of actions that many would consider legitimate forms of effective resistance. What’s perhaps most interesting is that the proscription of PA appears to be based upon parts of that definition that are pretty vague and, so far, don’t seem to have called for such action. Here’s the definition of terrorism for the purposes of the proscription act:

“Terrorism” as defined in the act, means the use or threat of action which: involves serious violence against a person; involves serious damage to property; endangers a person’s life (other than that of the person committing the act); creates a serious risk to the health or safety of the public or section of the public or is designed seriously to interfere with or seriously to disrupt an electronic system. The use or threat of such action must be designed to influence the government or an international governmental organisation or to intimidate the public or a section of the public and must be undertaken for the purpose of advancing a political, religious, racial or ideological cause.

(Source: Gov.Uk website, emphasis added)

The vagueness I’m referring to is the phrasing of ‘serious’ with regard to damage or risk. There are precedents set each time a definition of ‘serious’ is made concrete, as it is with the proscription of PA. The level of property damage PA has conducted is pretty high (estimates of tens of millions) and is perhaps most easily comparable to the ALF (Animal Liberation Front), an organisation that was active from the mid-seventies through to the nineties. The ALF itself was never proscribed. Individuals were prosecuted for criminal acts, but the organisation itself was never proscribed. Nor was proscription used against other deployments of direct action and property damage, whether that be XR, JSO, Reclaim the Streets, the anti-roads protests, the NUM during the miners’ strike, CND, Greenham Common, Trident Ploughshares, or the Angry Brigade, to name just a few instances when direct action tactics were used. Only in the case of the war in Ireland was proscription regularly deployed.

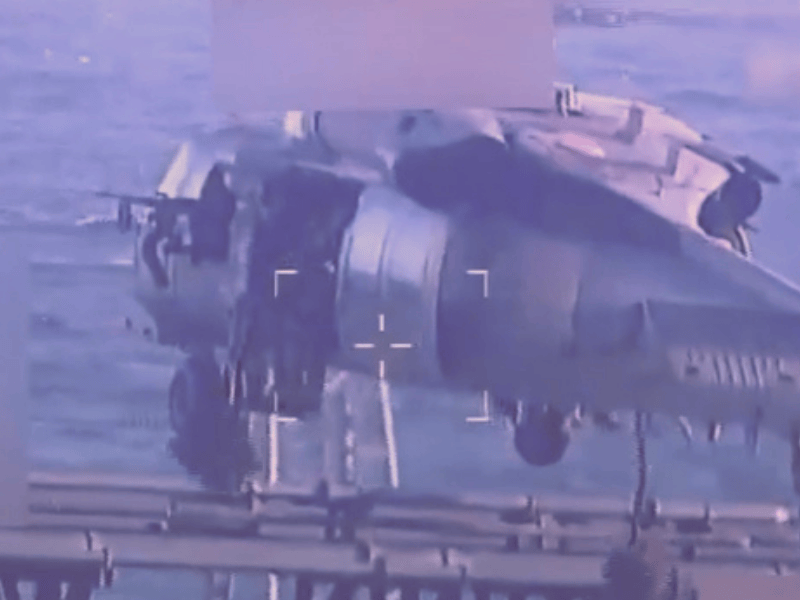

Two things stand out with regard PA, however. The first is the extremely high degree of effective damage caused, with estimates of tens of millions of pounds, higher in just five years than the ALF achieved over twenty five years. The comrades of PA were effective, that’s the first point. The costs they imposed on the system were not insignificant. The second moment to note is the targets chosen by PA. From the beginning in 2020 the main target appears to have been Elbit systems. It’s the shift to the target at Brize Norton and the attack on British military hardware that is potentially the key factor in the timing of the proscription. Whilst the state might try to punish damage caused by direct action against private companies, direct attack on its own military infrastructure apparently causes it to lose its mind.

For the resistance this is important information. If one of the effects of the proscription of PA could be a ‘chilling effect’ on future uses of direct action, then it’s important for those considering such actions to not over-compensate. PA have been conducting direct action against Elbit for years and so it’s a poor inference to assume that the proscription is a response to direct action in itself. It’s far more likely that it results from the choice of military targets. However, such speculation can only be evaluated in actions and at huge risk. In practice the caution of self-preservation is likely to make people view any form of direct action, particularly the non-symbolic form of direct cost extraction, to be too much of a risk.

More speculatively and to a degree more dependent on the level of social support, there is potential for the proscription of PA to provoke a Spartacus moment. It’s not inconceivable that there might be enough of a response to the legislation as to make it a high confrontation event. If a million people were to begin claiming they were PA, using the imagery and flouting the law, such a provocation could render the whole legal structure of proscription impotent or at the very least break the common sense that allows it to be used with relative impunity by politicians. It’s difficult to actively advocate and organise such a move, however, without a widespread degree of spontaneous resistance. Such spontaneous resistance is not inconceivable and should be keenly watched for and responded to.

Where next for direct action?

If we accept that PA are in the firing line in part because of the effective costs they have imposed, and the wounding of the state’s military machine, it may be time to develop new forms of direct action. One reason that the ALF may not have received the same form of repression is that it was a radically decentralised form of resistance. In effect it was a name that anyone could use to focus the point of their action. It may be that such informal organisation is one way forward. By its very nature as an informal focal point, such a tactic is not one that can be easily deployed, however. It results from a process closer to the spreading of a meme than traditional political organising.

Two other forms of direct action might also need to be revisited and explored. On the one hand the mass blockade, which is again a kind of focusing tactic, centred on specific times and spaces rather than on an activist grouping. PA’s method of action appears close to the tactics of JSO and to some degree XR, where small groups of activists carry out a variety of attacks, allowing a high degree of coordination and flexibility, but at the cost of putting the activist in a semi-sacrificial position. This is a valid tactic of course, but it might be reaching its limit. Coordinated mass blockades, shutdowns and sieges may be a way of keeping high confrontation and effective direct action, although these tactics have been used widely in the last twenty years and have themselves reached a crisis point in terms of their effectiveness. The start-up costs of such mass blockade actions are considerably higher than in the case of the tactics deployed by PA, however. More people need to be involved, with more labour of organising behind them.

The other tactic may well be a renewal of the strike, in particular what Plan C has described as the ‘social strike’. This concept has more than one element and can be interpreted in different ways. One element, for example, is the idea of extending a strike in a particular industry beyond the workers directly involved and into the community and the social structures surrounding it. In the case of nurses and doctors for example, connecting action in the NHS to the communities and relations that the industry is embedded in can offer a way to enhance the social, political as well as economic costs of a strike for the bosses and politicians. It can strengthen and politicise strikes in sectors that work as part of the social structure. It can also add power to workers by providing widespread material support for those on the frontline of a fight.

Another element, however, might be the extension of the targets of strike action beyond the directly economic. In this case we might be thinking of the strike as the action of enough people within a particular social space against any target of power. This is closer to a version of mass non-compliance, which might take the form of shutting something down – blocking – or making something unworkable via forms of refusal. Mass co-ordinated non-compliance is the core of an industrial strike tactic and is potentially capable of being extended into other social spaces. The anti-Poll Tax movement was perhaps one such example, the Don’t Pay campaign another. The difficulty here is in breaking such actions away from an individualised form of resistance into forms of mass coordination, moving away from something like a boycott, which rests on a capacity to choose often unavailable to large sectors of the working class, towards the development of a mass political consciousness whereby whole communities begin to enact political choices directly rather than waiting for some politician to save us.

Whatever happens next, resistance will continue. We need to remind ourselves that everything in this world is made by us and can therefore be remade by us. Our creativity overcomes their repression time and time again. We are the water that wears away the stone.

Image: “Palestine Action protest, 1 May 2023 – 26” by Leicester Gazette, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0