Since the 2008 financial crisis it has become increasingly impossible to survive on wage labour. In real terms, wages in the UK have declined by 5.5 percent since 2010; the fourth worst in the European Union. Combined with the reduction of the social wage and chronic unemployment (and underemployment) the situation is worse than any in recent memory. Yet the vision of our emancipation offered by the traditional left, the mythologised return to full employment, seems near impossible in an age in which human labour is increasingly superfluous to the production of commodities. Additionally, when considering the centrality of debt to contemporary capitalist growth and the expansion of value-extraction to cover the entirety of social re-production and co-operation it is clear that the boundary between the ‘social factory’ and the factory proper, the productive and the unproductive subject, is blurred beyond recognition.

Remunerated unproductive labour, unremunerated productive labour and of course mass unemployment and widespread poverty demand a response that falls outside the purview of traditional leftist discourse. The universal basic income is one such response.

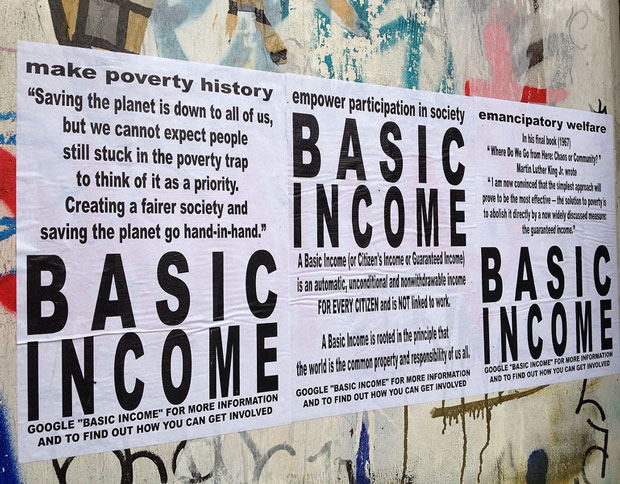

The universal basic income would ensure that everyone, regardless of employment, earnings, age and gender, receives a guaranteed minimum income from the state; a single weekly or monthly monetary payment with no stipulations as to how it, or the time of its recipients, is spent. Admittedly, the introduction of the universal basic income goes against the grain of the seemingly unstoppable neo-liberal current which has accelerated the dismantling of the welfare state and attempted to impose entrepreneurial individualism as the dominant subjectivity. Is it, therefore, unrealistic to envisage the implementation of a universal basic income whilst the very idea of the social wage is under attack?

It seems not. Recent developments in Cyprus, which have witnessed the announcement of plans to introduce a guaranteed minimum income, represent a trend of thought amongst a growing number of bourgeois politicians and economists (see Paul Krugman) that recognises the need to respond to the impact of automation on human labour, redistribute some of the gains of capital and ultimately stimulate consumption; all of which is aimed at the perpetuation of capitalism.

It must be noted that the proposals advanced by the Cypriot government are means tested and predicated on the inability to refuse employment, whatever its form or remuneration, or lack of. Although by providing a minimum income the policy does recognise the need for a basic standard of living its conditionality resembles that of workfare, albeit in a more generous form. This vision and likewise Krugman’s are not our own: ours if one of the unconditional granting to all, regardless of employment or the desire to find it.

Despite this dissonance, the seeds of communism are to be found in capitalism. Whilst acknowledging the limitations of the universal basic income as a stablisier of capitalism and its potential for instrumentalisation, we must recognise the new political and social possibilities that its implementation would offer.

Beyond immediate relief from mass immiseration the universal basic income is a reform that, although not capable of displacing capitalism on its own, sets the stage for the further radical transformation of society: in short, a non-reformist reform. Viewed as a wage stripped from production the universal basic income would not only destroy the mythical sanctity of work—itself a controlling ideology of capitalism—and the corresponding notions of reward and worth but also impact on modes of production, organising and the potential for human creativity. Such a shift has the potential to dramatically accelerate the discussion and struggle over what work is necessary, how it will be done and for whom.

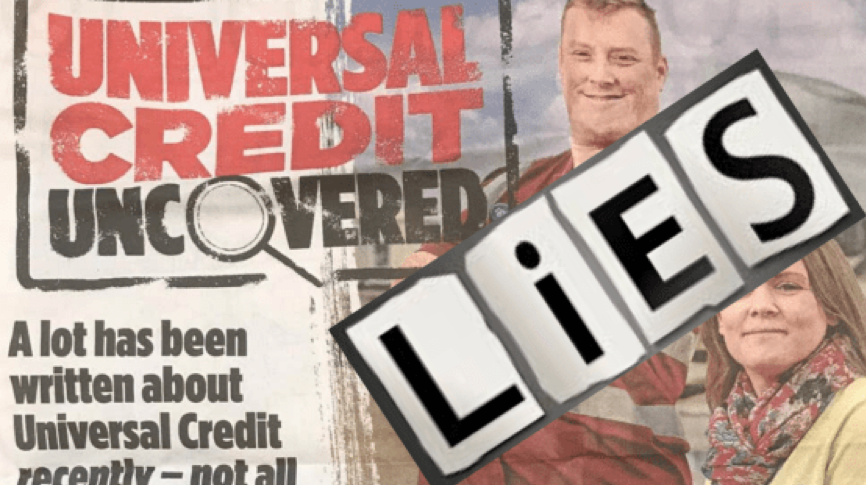

Those seeking to transcend capitalism should consider placing the universal basic income at the center of their discourse and action. The expansion to all of the newly introduced universal credit, its increase to the median income level and the removal of the conditions which dictate its receipt must be central to such a program.

This article was written by Thames Valley Plan C and is scheduled to appear in Issue #2 of The Exchange, a paper produced by members of the Anti-Capitalist Initiative. For more information on the basic income see basicincome.org.uk.