Radical Childcare: Speech given at The World Transformed Festival 2017 – Camille Barbagallo.

When we think about childcare, we can start by asking some simple questions. Like, who looks after the kids? Then ask, does it always have to be women? We can ask where the work of care takes place. At the moment the only options seem to be in the family at home or institutional settings. We can ask under what conditions do we do the work of care? Is it our job, that we receive wages for, or do we do it because that is what mothers are ‘naturally’ meant to do. Don’t forget we are ‘naturally’ meant to enjoy it as well.

While these questions appear to have simple answers – any attempt to discuss them politically quickly unravels. In fact, these questions are at the centre of what it means to be a mother and a parent. They also reveal how capitalism and the nation state has always relied on women’s work. Both our waged work and the untold hours we spend cooking, cleaning and caring for others. When we start to think about childcare as a political problem we are addressing the everyday issues that millions of households face across the country. Problems that disproportionately affect women with children.

In the first instance, I want to make an argument that childcare, and care more generally is more than just a set of policies that mean women can work for wages. We must start to think about care as doing more than just supporting maternal employment. The reason that this is important is that if we simply continue to create childcare policies so that women can work more, we end up, often unintentionally, degrading and devaluing the work of care. Care is work. It is hard, skilled and complex work that creates the possibility of life and labour. Reproductive labour is not just something to be escaped from, contracted out, often at the lowest cost. So that women can get back to, you know, ‘real’ meaningful jobs, in the ‘real’ world of work.

We need to demand that childcare provision be delinked from supporting maternal employment. From this starting point a whole host of new and interesting problems start to emerge. Especially if we also add into the mix the rights to care that all children must be afforded. We need to stop treating children as objects. Instead, we need to treat them as subjects who have a central role to play in creating change and determining their own lives. From this perspective we are also able to think about the needs and desires of mothers and parents who provide care in an unwaged capacity? How will they supported for the work they undertake? We need a universal living income that recognises the gendered way that care and reproduction is organised.

Delinking childcare provision from maternal employment doesn’t mean ignoring the needs of women who work outside the home. It means starting from the premise that all women with children and parents need access to social services like care. And that in a society dominated by capitalist social relations, we all need access to a independent income to afford us the dignity, respect and autonomy that we deserve.

Delinking childcare from maternal employment also opens up the space to think about care as doing something more than training our kids to be school ready, which is just getting them work ready. From this perspective care needs to not only be taken out the market but also outside of the interests of the market. As a directional demand, we need to end the transfer of millions of pounds of state funding being transferred to the for profit care market through the provision of 30hours ‘free’ childcare.

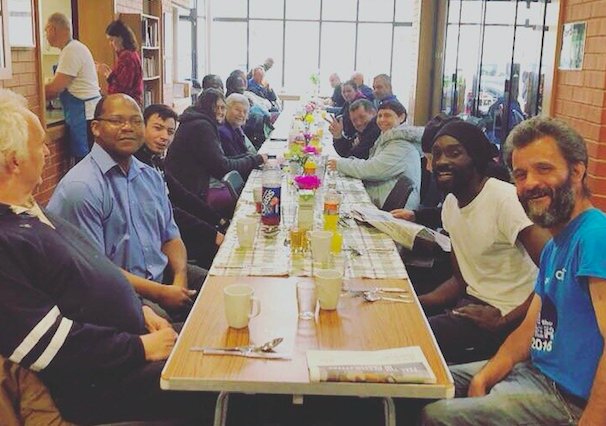

In contrast to giving millions of pounds to multinational corporations to provide the bare minimum of care that doesn’t actually meet the needs of working parents – another vision for care is not only possible, it is necessary. For example we could create Community Care Centres, that would be at the centre, both physically, politically and economically of our communities. Not just in the trendy, middle class parts of town, but in every neighbourhood. These Centres would not just involve the care of children, but instead be an intergenerational approach to care, that involves many of our elders and people with different abilities and needs.

The workforce would not involve poorly paid working class women. Instead such centres would be spaces of co-production and management undertaken by parents (many who are men), those without children, well paid workers and children themselves. As a community hub the concept of care would be centred on the needs of the people who use the Centre. As such things like the making of a collective meal once a day would be part of the work undertaken there, services such a laundry machines and breast feeding support. The possibilities are far from limited.

The question is how to do we get to such a vision of not only care, but also what it means to be a parent, a child or a worker. How do we build a movement that organises towards a red feminist horizon? Red feminism starts from the idea that reproduction and care are at the centre of our politics and lives. But, our vision of reproduction is one in which we have collectively refused those aspects of reproduction that are part of the problem. So that little girls can dream of being more than princesses. Boys will not just be boys, because boys grow up to the men. Men who will need more than just an understanding of consent and women’s autonomy. A red feminist horizon is one in which the work of reproduction and mothering is not devalued, undertaken because of love or reduced to ‘nature’ – but instead distributed among the community, revalued, supported and celebrated as the work that makes life and labour possible.

Enjoyed this? Check out our video introduction to Social reproduction here. Also, the audio recording of the event is here.