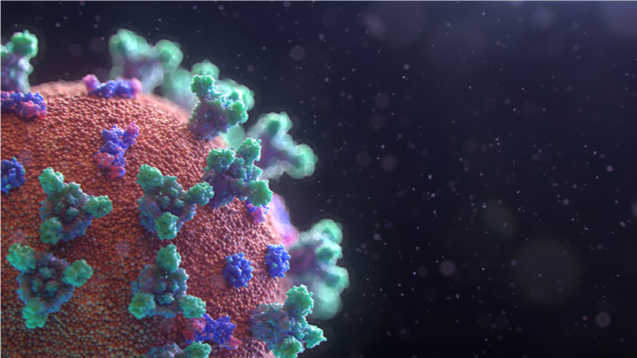

Don’t be fooled. Government responses to the pandemic reflect economic and political priorities.

By Cyril Winstanley

This is the second part of a two-part series of articles called From Marshall Plan to Martial Law. Here I look at how the government, although apparently united in the same aim as all of us (the elimination of the virus), is not our friend and how the state will use this crisis to further its dream of Martial Law and social control.

PART II: TO MARTIAL LAW

“As Princes do in times of action

get new taxes and remit them not in peace,

no winter shall abate the spring’s increase.”John Donne, c1603

“Soon there’ll be no dollars, no yens, no pounds,

just madness,

microchips and high-tech wars

and all because the beast wants to gain control

of every single mind, body, spirit and soul.’Roots Manuva, 1998

“There was also a political dream of the plague: … strict divisions; … penetration of regulation into even the smallest details of everyday life through the mediation of the complete hierarchy that assured the capillary functioning of power; … the assignment to each individual of his “true” name, his “true” place, his “true” body, his “true” disease. The plague as a form, at once real and imaginary, of disorder had its medical and political correlative discipline. Behind the disciplinary mechanisms can be read the haunting memory of “contagions”, of the plague, of rebellions, crimes, vagabondage, desertions, people who appear and disappear, live and die in disorder.”

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 1975

Poets have always said that humanity is one body. However rich or poor, death will come to us all. And so here we are, on the face of it, united in the same cause as the state. The state, commonly our oppressor, has now a common interest with us in eliminating this virus. There have been some objections to the war analogy but the comparison is apt in a sense. As our elders were in World War II, so are we now. We accept restrictions on our freedom which we would never submit to in “peace time”. But this acceptance does not mean that we trust the state any more than we did before. My enemy’s enemy may still be my enemy.

We do not run our own institutions

They are run by the state, or have been sold by the state to corporations. NHS workers must follow directives devised not for their safety but in order to manage resources, whether human or material. Workers have been told off for changing their contaminated PPE too often or told not to wear it at all. The NHS is not “ours”, it is the state’s. For us, the problem of corona is how to preserve life; for the government, how to preserve the economy and, as always, how to preserve themselves. We, the innocent (or not so innocent) herd, must be watched, nudged and fined into compliance.

In many ways, they have us where they want us. Confined to our houses, crime rates have gone down by 20%, the police tell us. Working from home, many desk workers have found themselves working harder and being more monitored than they were in the office. Microsoft software records when they clock on and clock off, how long their breaks are, and how often they take them. Many have lost work, but this mass of the newly unemployed are not yet a serious social problem, isolated as they are indoors, and occupied for a while wading through the bureaucratic mud of the swamped benefit system.

The problem for the state is the drop in consumption. Advertising hoardings are no longer exhorting us to go out to buy experiences, beauty, sexual partners, etc. but instead roll out advice on staying at home or make insipid calls for applause for “our NHS” heroes. We are no longer burning fossil fuels to get to places, nor staying in hotels or eating in restaurants. Parts of the economy are doing well, however. Still, our rents must be paid from somewhere. Still, we feed into streaming sites and click for something to occupy us during lockdown, hooked up on Netflix, ordering things through Amazon. We queue for supermarkets, where trade is booming.

New forms of subjectivity

Our ability to produce our own culture is challenged. Already, it was compromised by the gentrification of areas and the conversion of venues into flats; by the high prices of alcohol and the monopolisation of corporates. The end of university grants, squatting and a permissive dole on top of a tightening of immigration controls have dried up some of the working class routes into arts, which the effects of democratised music, video production and social media have only partly mitigated. Now we can only consume via our screens.

Humans’ remarkable talent for creativity and adaptability has overcome some of our problems. Likewise, neoliberal capitalism has overcome some of theirs. The trend, especially since the internet era, towards the privatisation of consumption without the camaraderie of market stall, rave, pub or place of worship, means the economy was partly ready to adapt to the new arrangement anyway. The internet, it must be said here, is a battleground to be fought over. In the case of social media, it may already be hostile terrain. As our late comrade Mark Fisher wrote, “the obsession with the web, its monopolisation of any idea of the new, has served capitalist realism rather than undermined it.” The internet’s potential for monitoring and surveillance is obviously of benefit to the state; as is, for bosses, the fact that work can follow you home, leaving us, in Mark’s words, “exposed to work’s order-words when we are alone, without the possibility of support from fellow workers.” The web’s disconnected bubbles in which we float leave us thinking we are communicating with others, but really talking to ourselves.

This is not to say that we should unplug from the matrix and throw our laptops and smart phones out the window. The internet is of immense use to us. Yet, some of the ways in which we use it (or are used by it), means that Mark was right to point out that, as well as its democratic benefits, it has also “generated pathological behaviours and forms of subjectivity which not only generate misery and anger – they waste time and energy, our most crucial resources.” Mark concludes that we should not “abandon the web, only that we should find out how to develop a more instrumental relationship with it. Put simply, we should use it – as a means of dissemination, communication and distribution – but not live inside it”. The lockdown increases the possibility of the latter.

It has been pointed out to me that, for a significant minority, the internet is a safer and easier medium through which to socialise and the place where friendships are made and maintained. It is important to be reminded that there are some people who prefer to manage relationships through the medium of the screen. Equally, though, we must also remember that there are a significant minority who, through unfamiliarity or lack of access, are barely able to use the internet at all. Thus, some people manage the transition from actual to virtual communication better than others.

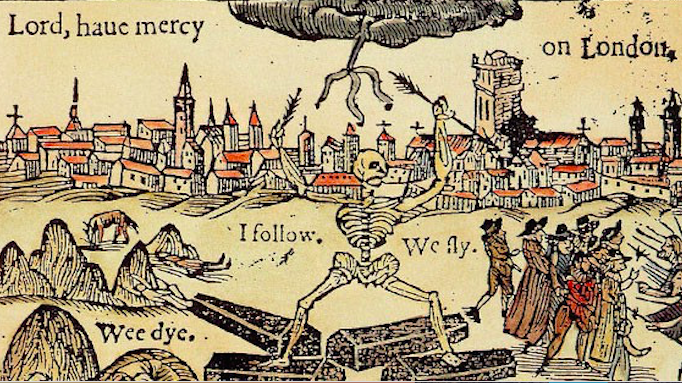

Pandemics are distinct times

We are living in one and, as French political theorist Michel Foucault said in his classic history of the prison, Discipline and Punish, therefore also living in the “political dream of the plague”: the quarantined town where everyone is in their place, all movements and all conditions regulated, observed and reported upwards to a central authority. The Tory government are enthusiastic for this kind of dream. They have suspended parliament (as the prorogation of 2019 shows they wanted to do anyway) and granted themselves new powers (and MPs £10,000 for the expenses of working from home). They even have their martyr in Saint Boris of Johnson who has miraculously risen from his hospital ward on Easter Sunday. We have our own dreams, of course, and there are plenty of subversions of theirs but we should be aware what is being dreamed up for us.

Pandemics are distinct times, but not, as everyone seems to be claiming, unprecedented. There have been many plagues and pandemics in human history. Foucault quotes from 17th century regulations of the plague-struck town of Vincennes, where the only people whom the authorities allow to move about the streets are those enforcing security and the “people of little substance who carry the sick, bury the dead, clean and do many vile and abject offices”. How unprecedented is this lockdown really?

To Martial Law…

United, as I said, in the common cause of eliminating the virus, we have proved ourselves compliant in working towards the sensible objective that is in everyone’s interest. Many of us were doing this before it was mandatory. Children stopped going to schools before they closed, many of us cancelled public meetings and stopped socialising before we were required to. We share the need to end the plague. However, there are interests in play which we cannot share.

The police have not been empowered as such, but emboldened. They already had almost unchecked powers (no cop has gone to prison for murder in this country in over 1,700 killings). They are limited only by what people will tolerate. In recent years, they overstepped the line with kettles and stop and search, until the reactions to the deaths of Ian Thomlinson and Mark Duggan made them step back a bit. In the cities, the youth know the power of 2011’s rebellion, and know how to record police abuse and conceal their own faces. Communities who have been used to harassment are little impressed by the police’s pretensions. Of course, the balance of power was always with the police anyway but now they have a new role. Being allowed to fine people at their own discretion elevates them from mere constable to magistrate. Although this mission creep was happening already, the police can feel more legitimate in moving beyond their official powers to arrest and detain, towards actually administering and executing justice. This emboldened feeling is dangerous. Police Twitter pages boasting about their corona patrols finding a small piece of cannabis, or regulating what they consider are “essential” items for someone’s supermarket trolley appear to show they are enjoying the new status.

We had better believe that a government that thinks in terms of meritocracy, eugenics and behavioural psychology sees a herd, and probably wants a flock. It needs, and well-rewards, its sheepdogs, not just with monetary treats, but with pats on the back and speeches about their bravery and good deeds. Sometimes, from certain perspectives, moreover, these sheepdogs look like wolves. Particularly from Black and working-class perspectives, allowing (as I hope you’ll understand) for the intersections.

It has not been the state that has first moved to protect us

It was feminist groups who first pressed the need to mitigate the inevitable increase in domestic violence that a lockdown would produce. Yet, it was only on the Easter weekend that Home Secretary, Priti Patel, announced measures to deal with it. Her announcement that the police will save women from abuse is unlikely to inspire confidence. Southall Black Sisters and Compassion in Politics took the initiative to persuade hotel chains to open up their empty rooms as refuges and, as a result, “hotels and specialist services are ready to support abused women and children. We are waiting for the government to play its part”. Rather than funding this, however, the Home Office, Patel told us, will publish “adverts raising awareness of where people can seek help on social media”, and spend “£2m to bolster domestic abuse helplines and online support.” With the charity Refuge reporting “a 700% increase in calls to its helpline in a single day”, the government is offering victims a phone line and asking the public for “solidarity” through a Twitter hashtag. The state’s indifference to femicide continues even in so-called “unprecedented” times.

Abolitionists and prison reformers at the start of the outbreak called for the release of as many prisoners as possible. Whatever your views on prisoners, none of them have been sentenced to exposure to a potentially deadly virus, yet no doubt nearly all of them have been dangerously exposed. Belatedly (and too late) the government did release some prisoners because, here again, our interests are united. The spread of the disease in overcrowded institutions, with workers coming and going every day, hastens the dissemination of the virus among the general population. Similarly, refugee groups called for the release of detainees in so-called “Immigration Removal Centres” at a time when there are no flights to remove them. Eventually, some have been released. Our interests converge, but not our aims. Can the government expect our solidarity when they have none with some of us? They will have my compliance with restrictions many of us were choosing to do anyway while the Prime Minister was still blathering about hand-shaking. Many of us had to push our bosses to allow us to work from home before it became obvious, even in the official narrative, that we were right.

As the numbers of deaths in the UK climb above 10,000, it has been shown once again that the state will not protect us. Yet, because of the power they have, the choices the state makes affect us hugely. As neighbours, friends and family or as professionals in a caring profession or in key infrastructure, we are supporting each other in many ways, but the state has the hospitals, the scientific modelling and the finance to manage our healthcare. They chose laissez-faire in matters of public health until it became a crisis, chose “Brexit over breathing” when it came to joining an EU order for ventilators. They are choosing authoritarianism in matters of social order.

John Donne wrote in the Elizabethan era of rulers using a time of war to levy “special” taxes which are not then taken away once the war is over. In these times, at the end of the second Elizabethan era, similar dangers apply. The Coronavirus Bill grants extraordinary powers for two years – much longer than the lockdown can conceivably be in place. However, we must take hope. Donne uses the case of never decreasing taxes as a simile for his never decreasing love. We must learn from this crisis to find collectivity again. The mutual aid groups we have established will be just as useful in “peacetime” as they are during “war”. We must remember how the state functions, how it dreams, as both Foucault and Roots Manuva said, of the “penetration of regulation into even the smallest details of everyday life”, of taking “control of each and every mind, body, spirit and soul”.

No doubt, if the UK had emerged from this with a lower death rate than the rest of Europe, the government would be trumpeting about their expert management of the situation. They have inexpertly mis-managed this so that the UK is now leading the way in deaths. The state has abjectly failed in managing our safety or manufacturing the right equipment. All they are good for is managing the “narrative” and manufacturing consent. Hence the advertising billboards and touching talk of our philandering Prime Minister’s pregnant fiancée (the same fiancée for whom worried neighbours called the police when she was shouting “get off me” and “get out of my flat”, and he was telling her to “get off my fucking laptop”). The media’s compliance in calling to depoliticise the discussions (i.e. not challenge too much the official narrative) is no doubt helpful in maintaining Johnson’s mysterious public appeal.

On Johnson’s return from his sick bed, the BBC opinion was that, “Agree or disagree with the way the coronavirus outbreak has been handled so far, Boris Johnson is the elected prime minister and political authority ultimately rests with that office. And authority will likely be what’s needed when big decisions lie ahead.” Only a fool would trust a person with authority with whose management they disagree. Leaving authority to make “big decisions” has so far proved disastrous. How can we trust them to end the restrictions at the appropriate time when we can hardly trust them now to give us accurate death statistics? To borrow a distinction from Judith Suissa, we must distinguish between those who are an authority and those who are in authority, and dream of a world where we collectively take authority for our own lives.