By Iida K

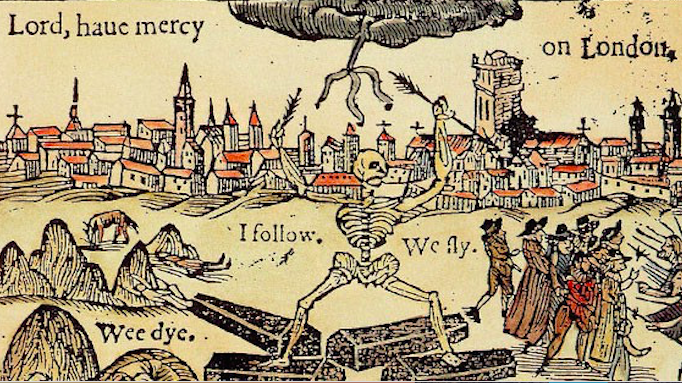

Times of crisis give rise to emergency powers. The main function of these powers is to extend the capacity of the state to control the population. The state is built on one central premise: the provision of security for its population, in exchange for obedience and loyalty. This social contract might at times be less apparent, but it takes centre stage in times of emergency. What we’re witnessing now is every right-wing politician’s dream: a chance to bring in unrestricted state powers under the guise of security for the people.

For the left, this means a firm commitment to creatively and deliberately turning down what the state has to offer. While we — necessarily — criticise the state for not providing adequate support for workers, renters and those made even more vulnerable by the pandemic, now more than ever we must remember to criticise the position of the state as the only possible provider of much of this support. Our revolutionary imaginations usually extend far beyond the confines of the state, and a pandemic is no reason to shrink ourselves into a governable mode.

Coronavirus as a threat to the system

From the beginning, coronavirus has been framed as a national and global security concern. The WHO called it “more powerful in creating political, social and economic upheaval than any terrorist attack”.[1] China’s authoritarian response to the virus involved a virus tracker app, linked to a police database, which issued each person with a colour code used to determine their access to public transport and shops.[2]

This combination of surveillance technology and increased government emergency powers[3] isn’t limited to China. National emergencies, enforced lockdowns and border closures are now the norm. The UK government, with its law and order fetish, won’t be far behind. We can already see the political opportunities the government is seeking to exploit in a time of crisis: police can now detain anyone they suspect of carrying the virus,[4] mass gatherings are likely to be banned,[5] and Boris Johnson plans to deploy the army to maintain public order.[6] These responses may seem appropriate in some ways, excessive in others — but, fundamentally, they’re building blocks for heightened authoritarianism. Don’t forget: this legislation is being passed without going to a vote, and is in place for two years.[7]

In the event the government begins to limit freedom of movement through border closures or lockdowns, it will be urgently necessary for us to respond with clarity. However much we agree with the importance of social isolation to stop the spread of the virus, let’s make one thing clear: the state’s security apparatus has actively and deliberately made certain people more vulnerable to the pandemic. ‘Security’ always endangers and targets a huge number of people with its processes of criminalisation, surveillance and imprisonment.

People in prisons, detention centres and secure mental health units face a massively heightened risk of infection. Undocumented migrants, and migrants generally, are far more likely to lack access to healthcare, or to be denied it as part of the government’s hostile environment policy. This is the reality created by ‘security’: it is the violence embedded in the operations of the police, the military and the justice system. None of it will keep us safe.

While it is important we make demands on the state that immediately support people in a time of crisis, we must be able to combine these demands with a wider political aim that seeks to undermine and overthrow the overall hegemonic project of the state. The threat the left faces is drifting into a reactionary mode, rather than mobilising toward a liberatory outcome. The danger of further normalising the state as the primary agent tasked with responding to the crisis is particularly apparent in discussions of border closures or lockdowns.

We would do well to remind ourselves that, even in exceptional times, some measures go too far to ever be anything other than violent or authoritarian. The space in which we want to operate is one that reinforces our own sense of power, rather than that of the state, and pushes for constant and vigilant scrutiny of the actions of the state — whether we judge them to be too much or too little.

Resisting security

What bolsters security politics is not just a sense of crisis and fear, but individualism and alienation. We’ve already seen the two sides in response to the pandemic: mutual aid organising on the one hand, panic buying on the other. The way to counter increased securitisation is not through shrinking our organising networks and installing more secure messaging apps. The only way we fight it is through destroying the logic that underpins state security.

We have to fight hard against the different conservative modes of politics that either make people want to insulate themselves and protect just their own families, or convince people that economic survival is more important than health care.

The first thing to do is recentre our energies away from the state and towards mutual aid and community organising. If we demand security from the state, we disempower ourselves and our communities.

Second, we have to fight the risk of mutual aid being co-opted into “good citizenship” — instead of building it into a project that sees us not as citizens in a social relation with the state, but as people relating to our common humanity.

This is the third step: political education and consciousness raising. Not top-down lectures, but discussions about why the state is failing us, and why it will always fulfil its promise of protecting only those in power.

The political common sense has shifted. Our demands — such as universal basic income and rent suspension — are being made by the political centre. This means we can be bold in bringing people with us further to the left — because many will have found their own way there already. The question is how to maintain the threat we pose in conflict with capital and the state as our demands are increasingly being met.

Just as the pandemic creates opportunities for the state to boost its own powers, it creates cracks in the system[8] — trials longer than three days have already been suspended,[9] for example. While state structures are slowed by the pandemic, we can hit the ground running with organising that will not only hopefully save lives, but also create a new political consciousness.

We know what the state will do in response to

crisis. It’s up to us to fight it.

[1] https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-is-the-worst-enemy-you-can-imagine-leading-doctors-warn-11931982

[2] https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-surge-in-apps-tracking-spread-and-symptoms-11948411

[3] https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-chinas-attempts-to-contain-the-outbreak-has-given-it-new-levels-of-state-power-133285

[4] https://metro.co.uk/2020/03/17/police-immigration-officers-can-12414089/

[5] https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/51918401

[6] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/british-army-standby-coronavirus-spread-200303113248092.html

[7] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-51916076

[8] https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2020/02/coronavirus-and-blindness-authoritarianism/606922/

[9] https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-criminal-trials-lasting-longer-than-three-days-to-be-suspended-due-to-covid-19-spread-11959367