The following blog piece on Libya and Italy, immigration, and the interests of an international ruling class, was written by plan c member, Richard B.

Since August 2017, the situation for Africans and Asians attempting to enter Europe without a visa has changed significantly. With the complicated but eventually effective enactment of a deal struck between the Italian and Libyan states earlier in the year, the infamous route across the central Mediterranean has been closed. It is most likely that the deal, reduced to its most basic elements, entails that the Italian state pay the Libyan state (and almost certainly with kick backs for various central figures in Libyan politics and business), as well as granting important concessions in the Italian-owned fractions of the oil trade, concessions favourable to Libyan state interests.

In this manner, the ruling Democratic Party have managed to return Italian-Libyan relations to the situation they were in from 2008 onwards, when Berlusconi struck a deal with Gaddafi, departures of irregular migrants from the Libyan coast were stopped, and thousands of black Africans massacred.

If the deal lasts, even for only a number of years, it is clear that a new historical chapter has been opened.

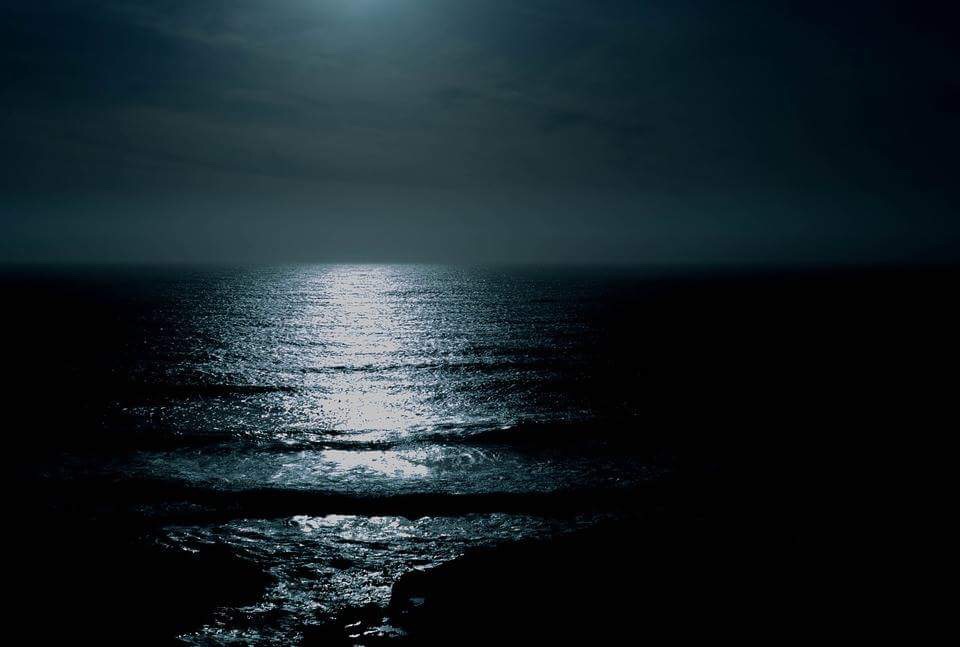

Here in Sicily, the rhythms of police, hostel managers, solidarity activists, passeurs, money changers and port authorities suddenly changed: a July full of the buzz of new arrivals, Moroccans sleeping in the porticos over train stations, young Somalians in the park by the sea, families moving across the bus networks, temporary prisons overcrowded… and then August went quiet. The tendering process for the new hostel contracts is going ahead, appointments at the police station still take months, even years. Yet the pace has altered. On all sides, there is both a sigh of relief, because perhaps the underfunded (purposefully underfunded) asylum seeker reception system can perhaps now function more smoothly. But there is also a breath of terror, a kind of dark eeriness about what is happening on the other side of the sea.

By now there are plenty of reports and images from the Libyan prisons. Quite how many people are trapped in them is entirely unclear, with estimates ranging from “several thousand” to “one million”, although this last figure represents a conservative guess at how many migrants there are in Libya in total – a generous estimate would put the number at three of four times that.

Life in Libya for these millions is often just as harsh as for the minority stuck in official or unofficial prisons. Indeed, there is a vast range of experiences even among this latter groups, partly reflected through the diversity of names given to their holding pens: camps, prisons, “Lager”. Imagery of the Holocaust is being repeatedly invoked by activists and journalists, in order to hammer home the brutality of events and try and rouse some kind of counteracting gestures. Certainly there are similarities, not least in the terrifyingly systematic nature of the violence: this is something you soon appreciate as you listen to the stories of those who have made the crossing, as they describe the same beatings, ransoming, slavery and herding.

But the dynamics of power are already in place, and any political opposition in Europe is likely to remain at only a gestural level, however incisive the allusions. The real forces at play here are capitalist: the manoeuvres of the traffickers, oil concessions, war. The increasing deployment of Egyptian troops along the Libyan border, with an eye to elections in Libya early next year and a possible gain for the Muslim Brotherhood, is more likely to have an impact on the future of the Central Mediterranean route into Europe than any leftist flag waving at this point.

When above I write that it is Libyan and Italian state interests which have determined the closure of the route, that is to say the interests of an international ruling class: it has become convenient for the capital on both sides of the Mediterranean to follow the same policy. This might collapse – for instance, through another military campaign in Libya, this time by Egyptian imperialism (always, in this epoch, under the guise of fighting terrorism) – or it might thrive, perhaps through the interest of Italian capital in the rebuilding of Libyan, in the manner that the rebuilding of Iraq relied on American capital.

As for Italian capital itself, the necessary reserve army of labour has been successfully established. Instead of bringing in hundreds of thousands of seasonal workers in for the harvests, as happened ten years’ ago, Italian agrarian capital (always in competition with French capital) now has its labour ready at hand. There are, quite simply, few workforces as cheap and as young as proletarianised West African men without documents (and therefore without the ability to make recourse to trade unions or state enforcement), attempting to send money back to their families. Thus, a balance has been struck between agrarian capital’s need for an impoverished labour force, and the metropolitan centres’ fear of this new proletariat rising up. It seems that these entirely subjective coordinates have a quite objective result: around 300,000 – more or less the number of working-class Africans and Asians who have arrived in Italy via Libya since the fall of Gaddafi and remained.

And so Italian capital is making its political alliances: the Libyan hell is being ameliorated by an Italian paradise. Over August – when the conservative ex-Stalinists in control of Italian migrant policy (Minniti and Orlando, the ministers of the Interior and Justice respectively) pulled the NGO rescue missions out of the water and sent the Italian navy to assist Libyan militia in capturing and dragging back departing migrant boats – the counteracting political force came from the Catholic left. A few days ago, however, the Pope changed his tune. Instead of opposing the closure of the only channel for people escaping to Europe from the horrors of Libya, he declared that it was understandable for “a country which has done so much, like Italy, to ask itself: can I host everyone? Do I have enough space?”.

The tactic is to accept Fortress Europe as a compromise for the acceptance of those who have already made their way into the enclosure. This is an attractive compromise for the Catholic Church as the battle ground of anti-racist legislation in Italy is its citizenship laws: the current “ius sanguis” allows only minors with an Italian parent to in turn claim citizenship. The proposed change would be a partial introduction of “ius solis”, allowing children who have grown up in Italy to claim citizenship despite not having an Italian parent. While clearly it ought be supported, the reform is just as clearly family-centric and patriarchical. The compromise the Catholic left is prepared to make, therefore, is that if the Stalinists give way on the most conservative aspect of anti-racism, they will give up on defending its more radical version, that is, the defence of freedom of movement.