By Lorenzo Feltrin, a Plan C member.

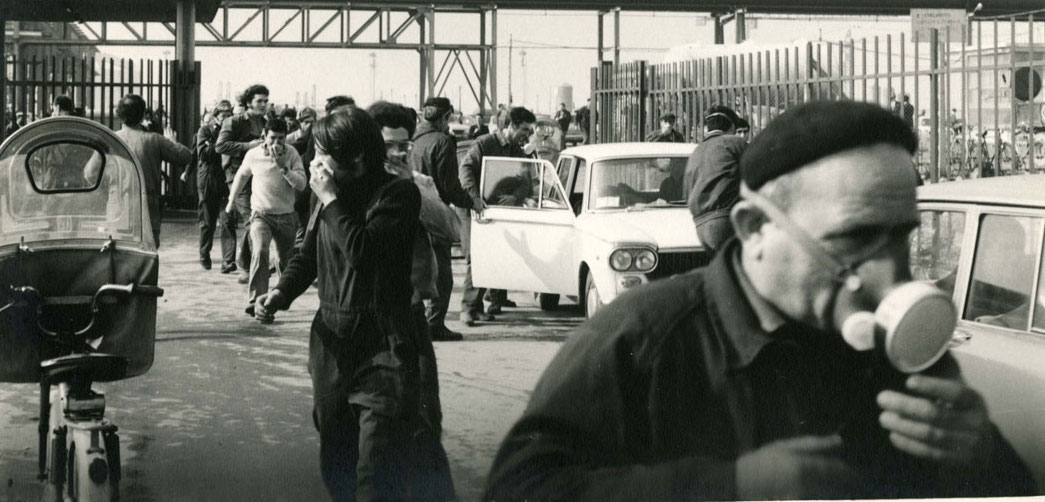

Photo by Tim Maynard.

Are the climate strikes “real” strikes? The answer to this question depends on our definition of what a strike is, which is in turn based on our political objectives. It is proposed here that the climate strikes, just like the women’s strikes, are part of the process that we call the “social strike”.

This argument rests on two theoretical assumptions:

-An expanded conception of work and of the working-class composition;

-A conception of working-class interests as encompassing both production (the making of commodities) and reproduction (the making of life).[1]

A strike occurs when workers withdraw their labour to pressure private employers or the state to make concessions. If we understand work as exclusively waged employment, then a strike only happens when waged employees perform a workplace-based suspension of production. However, if we adopt a broader definition of work, encompassing all activities – waged and unwaged, productive and reproductive – that are subordinated in both obvious and hidden ways to the accumulation of capital via profit-making, then work is not contained only in formal workplaces but is also diffused throughout society. It is done within households and communities (for a moment, just think of all the cooking, cleaning and caring that we call reproductive labour); through the means of communication (the production of data, emotions, entertainment, ideas that are captured and sold for profit by the internet giants); in schools (the formation of a labour-power adequate to the needs of the economy); etc. The social strike then, refers to a withdrawal of all kinds of labour, including labour in its most socially diffused forms.

A common mischaracterisation of the social strike idea is the accusation that, by giving to unwaged and reproductive labour the same “dignity” traditionally assigned to waged productive labour, it abandons all aspirations to fight the class struggle in workplaces. To the contrary! There is no reason why we should not strive for a social strike that touches upon the whole spectrum of work. The disputes about the primacy of this or that form of work appear as pointless to many of us, with the only concrete outcome of dividing us further. After all, work in capitalism is not a question of dignity but of coerced profit-making and social control, and as such it is a disgrace. Dignity is asserted by workers as resistance, overt or covert, against the toll work takes on life.

Another accusation sometimes made against social reproduction theory is that it is an attempt to save Marxist categories from a world to which they no longer apply, by trying to pigeonhole non-class-based subjects and struggles in a straightjacket of class analysis. The first response to this criticism could be a simple “Look around you!”, look at how our lives are shaped by steep social inequalities, economic crises and restructurings, and more importantly look at the sheer amount of time of our lives we spend working; and not just in paid work but in many other areas. But additionally, while in our perspective reproductive labour should be seen as included in a relation of exploitation, there is much to be gained by expanding what “working class” means, not just beyond the wage but also beyond exploitation. This can be done meaningfully by basing the class relationship on dispossession rather than on exploitation. Workers, then, are all those who are expropriated from ownership and control of significant magnitudes of capital. As Simon Clarke wrote, “all of the dispossessed are potential wage-labourers for capital, and in that sense are members of the working class”.[2] The threshold of “significant” is, of course, virtually impossible to establish in a clear-cut way, leaving space for a wide “grey area”, the middle class, in which the class relationship cuts across single individuals. Quantitative accounting, however, is not a concern here.

Class can be defined in manifold ways, and definitions cannot be proved or disproved by empirical evidence. Therefore, different conceptions of class should be judged on the basis of their political effectiveness and, for such purposes, a fetishism of the factory and the wage is scarcely useful, as such social relations don’t deserve much glamour. A useful definition of class needs to point to a set of potentially common interests that can realise a particular political strategy. Thus, the common condition of dispossession shared by all workers points to a potential interest in democratising ownership and control of the means of production.[3] This does not mean that all workers’ interests can be reduced to their dispossession, there is obviously a wide range of interests that cut across the class, based on gendered and racist hierarchies and on differential exploitation. It just means that even if the dispossessed are divided in many respects, they could find common ground in the overcoming of their dispossession, and a crucial condition for this to actually happen is indeed the empowerment of the workers at the bottom of the work-gender-race hierarchy.[4]

The standard argument for an exploitation-based definition of class relies on the leverage that exploited workers have. By striking, they can bring the valorisation of capital to a standstill. This is uncontroversial. However, workers worldwide have factually proven to have the capacity to hinder the production of value from the outside of the formal workplace too, through roadblocks and other forms of disruption. There is much to be lost in excluding these forms of struggle from the domain of class struggle. Class struggle is thus a much broader phenomenon than class-conscious manual workers’ collective mobilisations in the workplace. It refers to all contentious action – individual or collective, within or beyond the workplace, class-conscious or not – by people dispossessed of significant ownership and control of capital to assert their class interests vis-à-vis those owning or controlling significant magnitudes of capital.

Coming to the issue of labour and the environment, the stereotypical media-fuelled view is that of environmentally regressive workers defending polluting industries against middle-class activists who can afford to protest for clean air because they have nothing more pressing to worry about. To the extent that community-based protest is considered, it is treated as completely unrelated to class issues, as if the members of communities affected by environmental injustices magically did not have to work for a living. This kind of discourse is typically underpinned by a narrow definition of the working class as waged – or even solely industrial – employees and by an even narrower conception of working-class interests as solely based on wages and workplace conditions. This rests on the fiction that workers somehow vanish after they exit the factory gates, that they don’t have homes and communities to return to, that they don’t enjoy their free time by relating to the ecologies that surround them, that they don’t breathe the air outside the walls of their workplaces.

If we consider as working-class interests only those interests directly related to the workplace of waged employees, we are unlikely to escape the dilemma between workers’ rights vs. environmentalism and the idea of the “job blackmail”, in which workers are presented with a choice between renouncing the protection of their health and of the environment of which they are part; or losing their source of income. To the contrary, workers’ interests do not lie solely on their conditions of production but also on their conditions of reproduction. As Stefania Barca and Emanuele Leonardi argue, “working-class environmentalism is that form of activism that comes to link production with reproduction”.[5] The class struggle is not fought only at the point of production but also at the point of reproduction, and the strategic objective should be that of bringing together these two elements in order to break apart the system that has generated the crisis of reproduction we live in, to be the crisis of capital and live beyond it.

By now, you might well imagine that my proposal is that yes, the climate strikes, just like the women’s strikes, are very much real strikes. So far, however, the climate strikes have mostly involved the withdrawal of labour by “labour power in formation”, i.e. the students, and by people (often their parents) that, because of their working conditions, can take some time off from work without the backing of a union. The fact that, due to the racist division of labour, the people performing such jobs are over-proportionately white is probably not unrelated to the fact that, so far, the composition of the climate strikes has been accordingly over-proportionately white. These limits have already been acknowledged by the movement, and this is one of the reasons why the unions have been called by Earth Strike to support and participate in the strike of 27 September 2019, to extend the reach and impact of the mobilisation.

Environmental degradation in our society is systemic because the current system subordinates the production of use values to that of exchange values, and the reproduction of our lives to the production of profit. The costs of such environmental destruction are unequally distributed because we are differentially dispossessed from significant ownership and control of the means of production and thus cannot make democratic decisions on what and how is made, in a way that would meet our needs and those of the environment to which we belong and on which we depend for the reproduction of our lives. Therefore, environmental struggles do not need to be reconciled with class struggles because, in fact, environmental struggles are class struggles and vice versa. What we need is a politics able to break out of the job blackmail and defy the divide-and-conquer tactics that try to fragment such struggles into narrow, single-issue campaigns.

[1] More precisely, production refers to the direct making of commodities, which in capitalism have both use value and exchange value. This encompasses employment in commercial agriculture, industry and services. Reproduction refers to the making of life, which in capitalism is also labour power. The most important examples are child raising, housework, public health and education, etc.

[2] Simon Clarke, 2002, “Class Struggle and the Working Class: The Problem of Commodity Fetishism”, in The Labour Debate: An Investigation into the Theory and Reality of Capitalist Work edited by Ana C. Dinerstein and Micheal Neary, Hants: Ashgate Publishing Company.

[3] The very notion of what is in somebody’s interest, as opposed to actually expressed preferences, is itself not an empirical description but a political proposition and, when acknowledged as such, it is an attempt to persuade and definitely not an accusation of “false consciousness”.

[4] Additionally, I agree with those that are very much sceptical of the notion that such overcoming of class will necessarily be accompanied by an automatic annihilation of other forms of oppression, that need to be addressed on their own terms as well as in their relations to class.

[5] Stefania Barca and Emanuele Leonardi, 2018, “Working-class ecology and union politics: a conceptual topology”, Globalizations, 15 (4), pp. 487-503.